There is a balance that’s required, when you own, as I do, a national award-winning car that has been so feted for its preservation. Much has been written in the last decade or more about the importance to the collector car hobby of the unrestored car, which has given birth to the cliché, “they’re only original once.” At the same time, cars which are driven (I have put over 14,000 miles on mine) will require, like any vehicle, routine service and repair. I wrote earlier about my decision, twelve years into the ownership of this wonderful Alfa Romeo, to move away from strict originality, not in a haphazard or indifferent way, but slowly and deliberately, and only to make improvements for the sake of appearance or functionality without unduly disturbing that which should be saved.

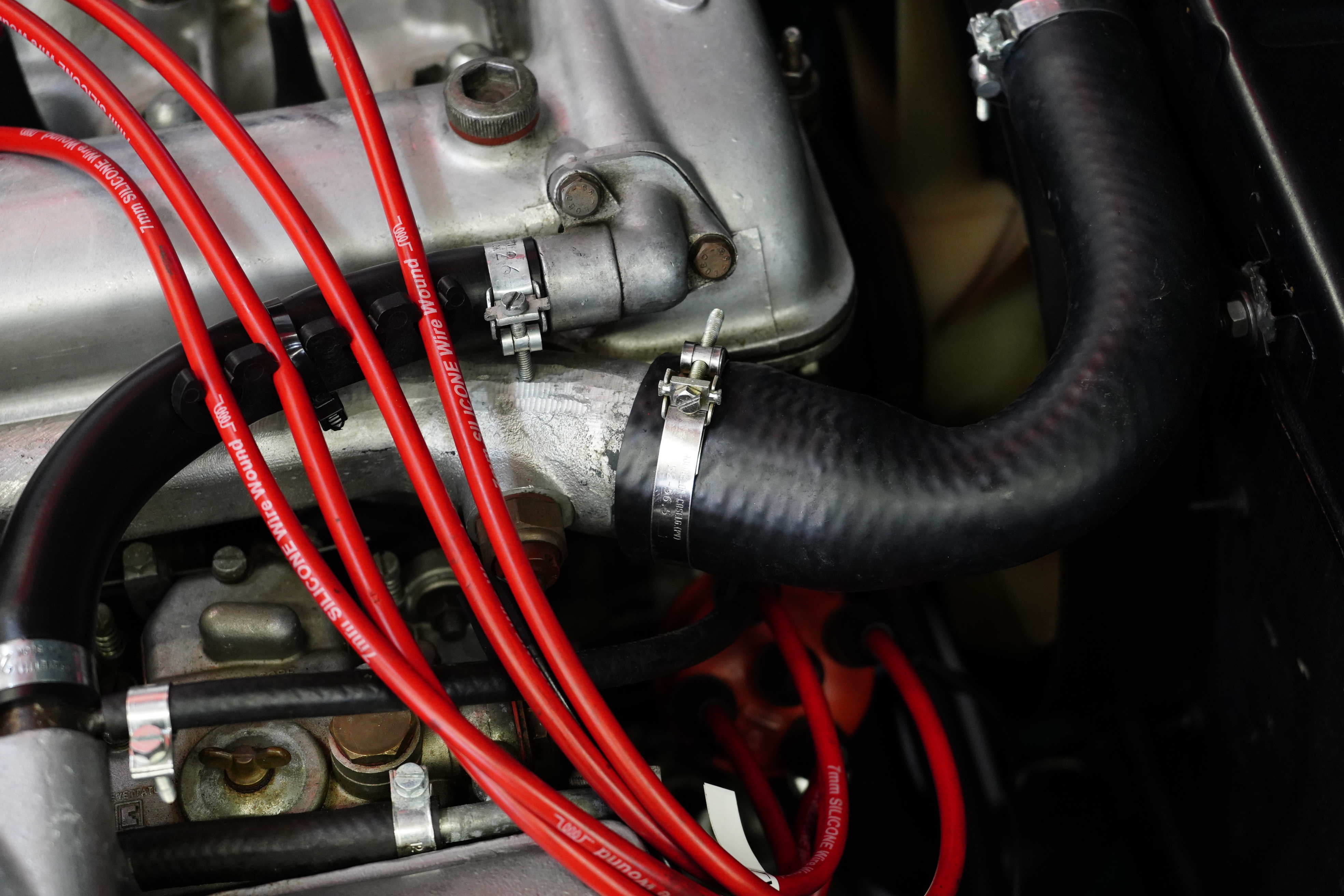

I thought about this again when in March, my wife and I hosted an AACA judging seminar at our home. My Alfa, standing in as a subject car for training purposes, was actually lauded for its “clean” engine bay. I know from attending numerous judging schools that AACA has high standards for engine compartments. Entering an AACA-eligible car in a national meet will ensure that several sets of trained eyes will focus on everything under your hood from firewall to radiator. While the average citizen defines “car detailing” as vacuuming the interior, waxing the paint, and cleaning the windows, AACA members know that in addition to those needs, the engine compartment must look like the day the car was driven off the new car dealer’s lot.

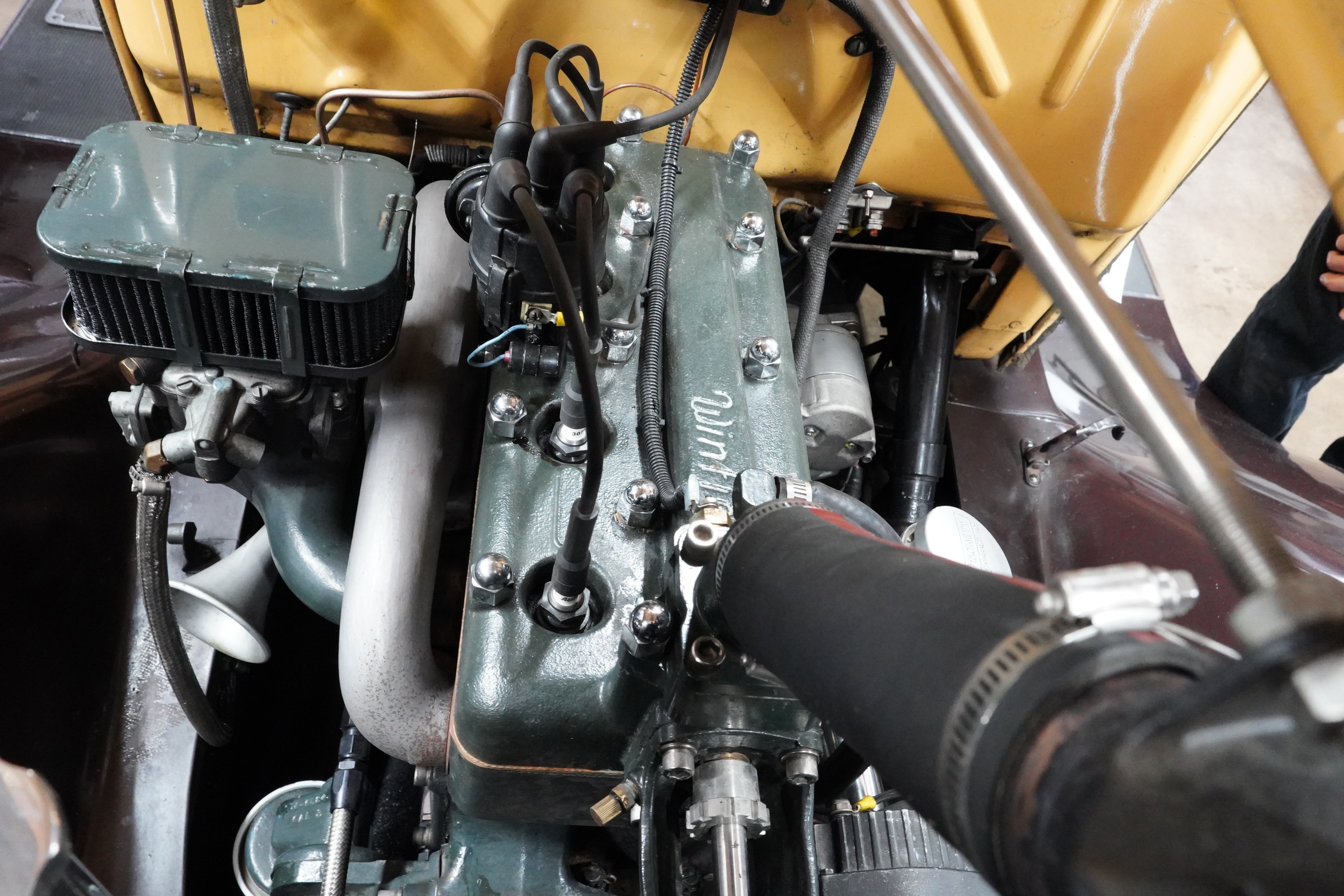

But I have accepted for too long that the Alfa’s engine and the bay within which it resides are “original, and therefore, not to be touched.” That has been changing, and most recently, my critical gaze fell up the quite unsightly air cleaner canister. It sits on the driver’s side of the car, over the exhaust manifold, and connects to the intake plenum via a rubber-and-cloth hose that passes over the valve cover. Mine is black, and it has been obvious to me since the day I took possession of the car that the canister had been repainted, possibly more than once, by a previous owner, most likely Pete, who owned the car from 1968 to 2013. To put it bluntly, the repaint was poor quality, with visible drips and runs. The black had also chipped off in several places. Frankly, it was one of the least attractive components under the hood. It was time to rectify that. Given that the canister had already been repainted at least once, I felt no qualms about stripping it down to the metal. There was nothing original to be saved.

Before I even removed the canister, I went to the national website of the Alfa Romeo Owners Club (AROC), where, as a member, I could access technical assistance. I emailed a Club volunteer who specializes in Alfas of the 1960s, and asked him what the air cleaner canister’s original finish looked like. He responded within twenty-four hours to say that the factory finished the canisters in semi-gloss black. (This was the first time I used this online technical service, and it’s a great perk of club membership.) Off to Lowe’s I went.

This was going to be a rattle-can job, which does not automatically mean “sub-standard.” I’ve had great success with the Professional line of Rust-Oleum spray paints, so I picked up a can of primer and a can of semi-gloss black. Out came the canister, which I doused with chemical stripper. Given the multiple coats of paint on the thing, this required several applications. Once I removed as much paint as possible with that method, I resorted to mechanical stripping with a 3M plastic abrasive wheel. The canister was down to bare metal, so I wiped everything with paint prep, and waited for a windless day to spray outside.

The primer went on smoothly and thoroughly, and it appeared that one coat would be enough. Next was the semi-gloss black, which had to be sprayed in stages as I rotated the canister for complete coverage. Two coats looked like plenty, and I saw no evidence of drips or runs. I gave the parts twenty-four hours to dry, and reinstalled the canister.

The improvement in the engine bay’s appearance was immediately obvious. If you look closely enough, you can probably tell that it was spray-painted, but to my eye, it looks sharp. My only concern, and it’s not a substantial one at the moment, is that exhaust manifold heat may cause the paint to flake. If it does, it will be the canister’s bottom, well out of sight of show-goers (and judges). If and when that happens, I’ll deal with it. In the meantime, a few hours of simple work, and $20 worth of hardware store paint, has yielded a nice upgrade to the Alfa’s engine compartment.

BEFORE

You can see the rough surface, runs, and paint chips throughout the component.

DURING

First, the chemical stripping.

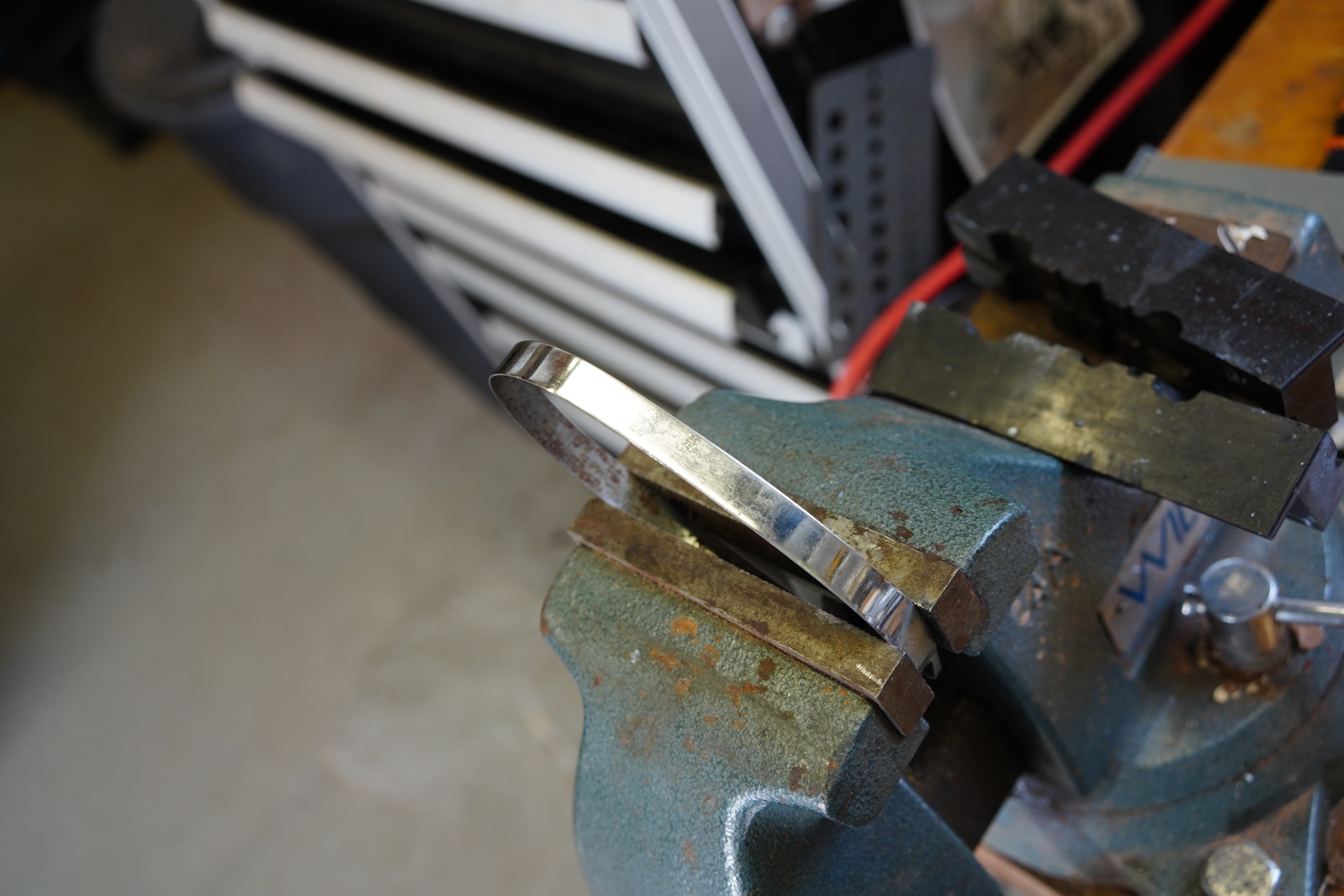

The remainder of the paint was removed with the 3M plastic abrasive wheel.

The primer coat.

The top coat of semi-gloss black.

AFTER

Once reinstalled, the canister looks much improved. For the most part, only the top lid is visible.

Entire blog post content copyright © 2025 Richard A. Reina. Text and photos may not be copied or reproduced without express written permission.