It is somewhat well-known among Miata owners that one of the few mechanical weaknesses of the car is its clutch hydraulic system. Typically, the secondary cylinder1 fails and needs replacement, and indeed, that component was already replaced once on my car, back in 2010. The good news is that the failures tend to happen gradually, and the driver gets significant advance notice as the clutch pedal gradually sinks while gear engagement becomes progressively more difficult.

I hopped into the Miata last week for the first time since winterizing it last autumn and in my case, the pedal was “gone”. Popping the hood, I saw that the clutch hydraulic reservoir was empty, although the dirty fluid left enough of a stain that one could be fooled into thinking there was still some fluid in there. I watched a few YouTube videos, several of which contradicted themselves (more about that coming up) and ordered a new primary cylinder, secondary cylinder, and flexible hose. All are Dorman products; one reason for the choice is that Dorman offers a lifetime warranty on the parts, when most competitors offer one year. The three parts cost me around $65 with shipping.

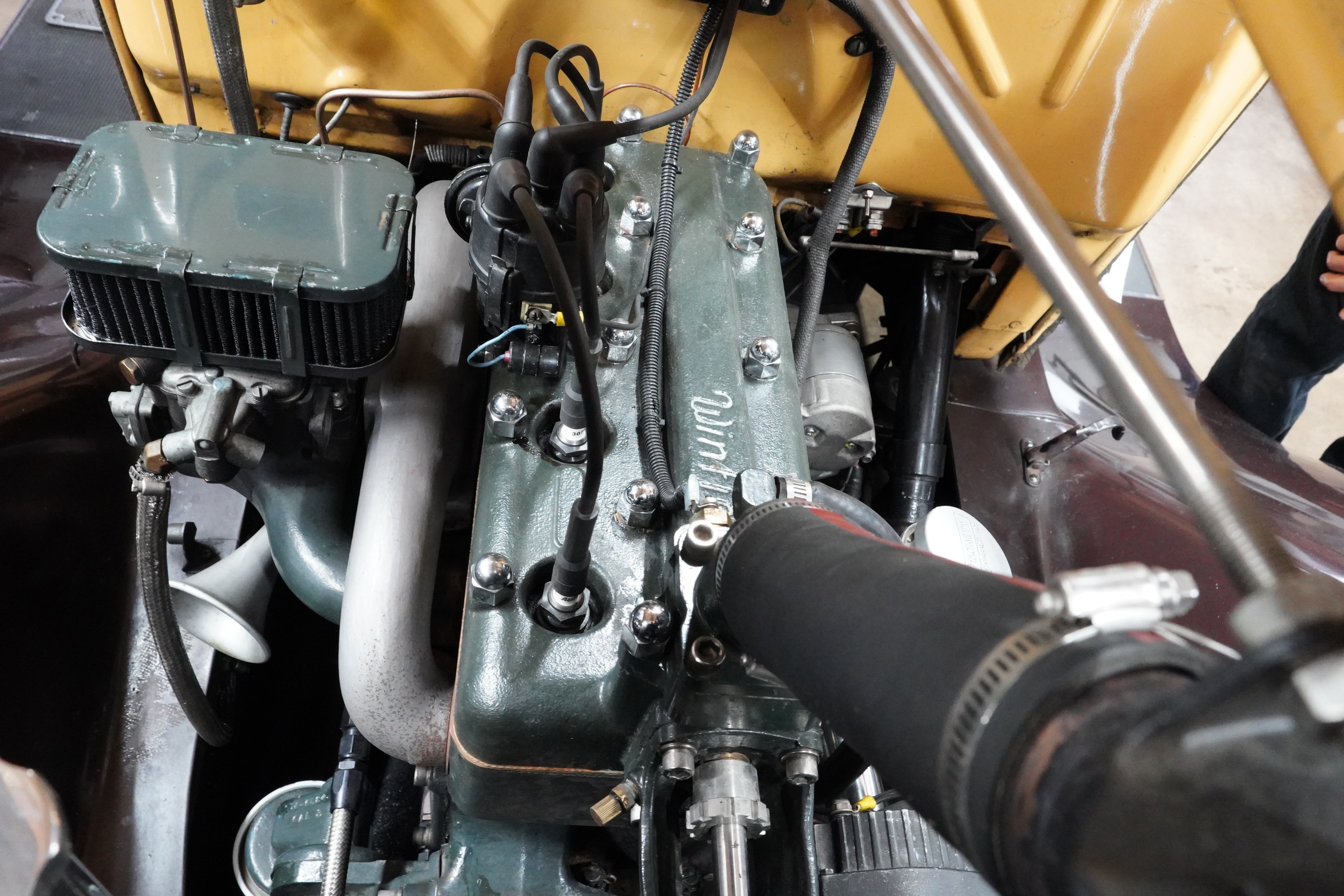

ABOVE: There are many cars where a single reservoir is shared by the brake and clutch systems, but the Miata is not one of them. The larger reservoir on the left is for the brakes. Note how clean that fluid looks, almost clear in fact. On the right is the clutch primary cylinder, and despite appearances, that reservoir is empty.

All exposed threads got a spray shot of rust-buster the day before, but none of the threads gave me a fight the following day when I put a wrench to them. The primary cylinder came off first: the fluid pipe fitting and two nuts were all easily accessible. Moving downstream, I tackled the clutch hose next. I had never really noticed this part before. In fact, it’s tightly tucked directly between the back of the cylinder head and the firewall. The pipe/hose routing is as follows: a metal pipe is routed from the primary, along the firewall, where it makes a 180-degree turn on the passenger side and connects to the hose. The hose runs back toward the driver’s side, held in place by two firewall-mounted brackets. From there, another metal pipe snakes downward to the secondary cylinder mounted low on the passenger side. (I suspect that much of this back-and-forth routing is due to the JDM (Japanese Domestic Market) Miata being RHD, and this lengthier routing was necessary to adapt to LHD.)

ABOVE: Primary cylinders laying side-by-side, old on left and new on right.

ABOVE: Old secondary cylinder on top, new one on bottom.

Why am I describing all this? Because these hose connections were a B – I – T – C – H to reach, something completely left unsaid in all the videos I watched. The video voiceovers cheerfully exclaimed “And then we replaced the clutch hose before moving to the secondary cylinder” or similar. I ended up disconnecting two wiring harness brackets to provide myself enough room to get a flare nut wrench on the hose ends. Several bloody knuckles later, it was done.

ABOVE: New hose on bottom appeared to be slightly longer, but that did not affect installation.

The secondary cylinder was the third and final piece of the puzzle. Without a lift, access required removing the right front wheel and squeezing my torso into the wheel well to reach the connections. As with the primary, there was only the threaded pipe and two bolts holding the cylinder to the block. After several hours of contorting myself, the R&R portion was done.

ABOVE: This was the easier of the two pipe-to-hose connections to access. Even here, A/C hoses and wiring harness run interference.

Next, it was time to call my able assistant who is well-versed in the “press – hold – release” mantra. My only regret is that I didn’t get a snapshot of Mrs. Reina as she sat in the driver’s seat and multi-tasked: left leg mindlessly going up and down on the pedal while she nursed a hot cup of tea and scrolled through her phone as it sat perched on the center console. And one more comment about the videos: one video insisted that bench-bleeding the primary cylinder was a necessity, while a second video declared it a waste of time. I chose to bypass the bench bleed, but before my wife came out to the car, I filled the reservoir, filled a small jar with brake fluid into which I inserted a hose from the bleeder screw, and left the screw loose. I then pumped the clutch pedal at least 50 times, refilling the reservoir once. This seemed to get a goodly amount of air out and shortened the length of time my wife was on the job. Thank you honey!

I took the car for a short spin and the clutch pedal felt marvelous. Let’s hope the hydraulics last another 10 years.

1Traditional automotive terminology has referred to brake and clutch cylinders as “master” and “slave”, terms which frankly have always caused me to wince. Here, because it’s my blog and I can describe things as I please, I have opted to refer to these parts as “primary cylinder” and “secondary cylinder”. I doubt it will catch on, but I would be eternally pleased if it did.

All photographs copyright © 2024 Richard A. Reina. Photos may not be copied or reproduced without express written permission.