Yesterday was spent rummaging through several plastic containers full of my parents’ “stuff,” as I pondered (and ultimately postponed) the idea of organizing hundreds and hundreds of my mother’s photographs (which go back to the 1940s) and arranging them in something close to chronological order. The real goal is to get them into photo albums so that my family can enjoy leafing through them.

But I did (re)discover several old postcards which brought back a rush of memories. I am in possession of two of my father’s postcards, both with images of Ford’s German Taunus 17M, one car a four-door sedan, the other a two-door wagon, both cars in a very ‘50s two-tone paint scheme. (The car was named after a German mountain range. Is it a coincidence that “Taurus” differs by only one letter?) I clearly recall my dad showing these to me when I was a mere pup. Both postcards are in pristine shape, and what’s especially intriguing is the setting, as noted on the back: “Rome”. Why would Ford produce postcards of its German-built cars with images taken in Italy? Given the use of English on them, I can only presume that these were produced for U.S. dealers.

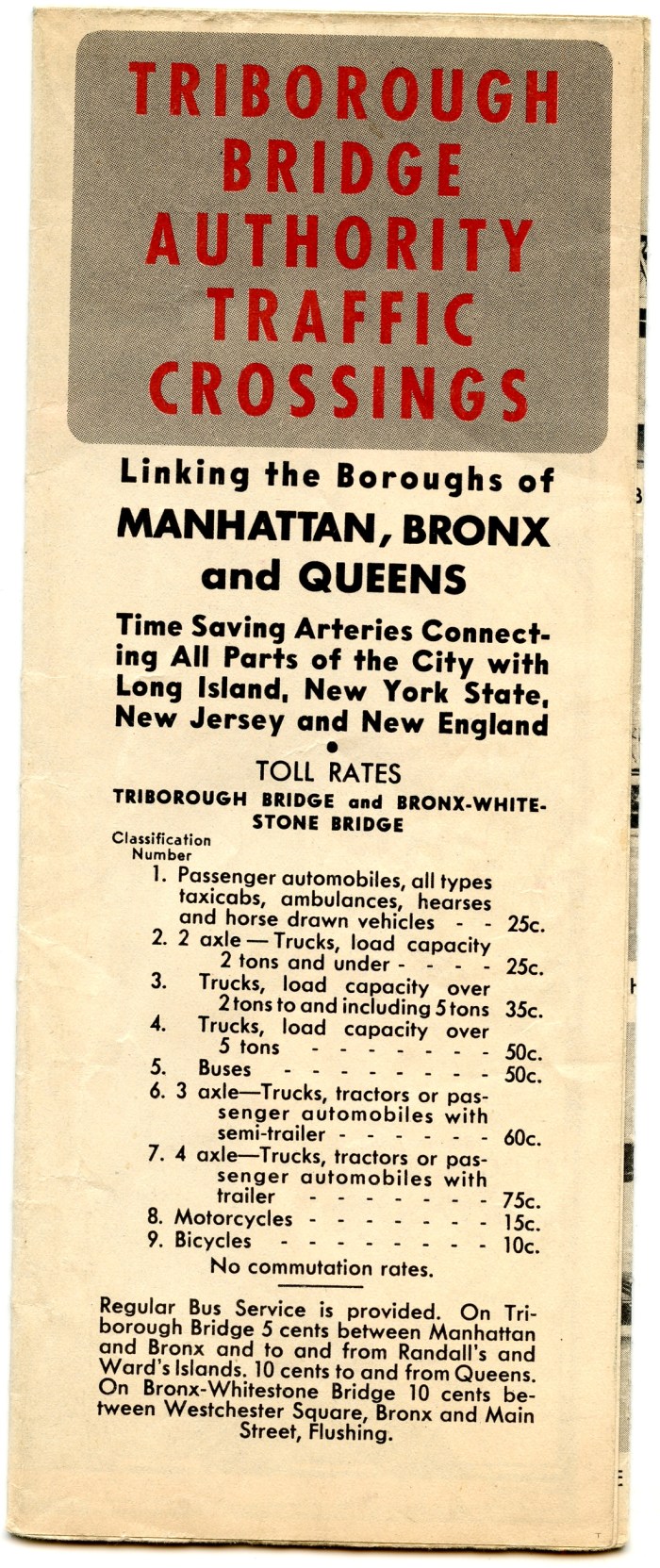

Since I know next-to-nothing about the Taunus, the reference books came out. My copy of the Standard Catalog of Imported Cars, 1946-1990 tells me that after several years of building Taunus 12M and 15M models, in 1958 the 17M model was introduced, with a larger engine and all-new styling reminiscent of American cars of that time. Out of a total of 67,772 units produced for global sales in 1958, 1,627 (2.4% of the total volume) were sold in the U.S. The 17M engine displaced 1698cc, and churned out 67 horsepower and 98 lb. ft. of torque. There were three body styles, two-door sedan, four-door sedan, and two-door wagon, each available in base or deluxe trim. Retail prices ranged from $2,017 to $2,311. The only options were overdrive or a Saxomat automatic clutch. These cars still used six-volt electrics, even though American Fords had already switched to twelve volts. The styling as illustrated in my photos remained through 1960, at which time the 17M was substantially redesigned.

As a final note, the book states that by 1961, “exports to the U.S. had diminished and Taunus was no longer listed as an official import. Not until the Capri of the 1970s and then the subcompact Fiesta did substantial numbers of Fords again arrive in America from Germany.” Of course, in model year 1960, Ford fielded its own home-grown compact in the form of the Falcon, as a two-door sedan, four-door sedan, two-door wagon, and four-door wagon. With a more powerful six-cylinder engine, and factory prices ranging from $1,974 to $2,225, the Taunus didn’t stand a chance against its domestic cousin.

Ford’s attempt to sell its European Taunus compact in the States is a long-forgotten memory for most. But as noted above, Ford would not stop trying, and General Motors (with its Opel) and Chrysler (with its rebadged Mitsubishis) would join the fray. The repeated attempts by U.S. auto manufacturers to sell imports in domestic showrooms is a convoluted story which continues to this day!

Entire blog post content copyright © 2025 Richard A. Reina. Text and photos may not be copied or reproduced without express written permission.