My buddy Enzo drove his 1991 Alfa Romeo Spider Veloce to my house this past weekend. He had requested my assistance with changing the transmission and rear axle oil in his car, and I’m always more than willing to assist a fellow Alfisti in need. This is not the first time I’ve worked on Enzo’s car, and in fact, we are both readying our Italian stallions in preparation for the trip to Pittsburgh in July for the AROC (Alfa Romeo Owner’s Club) annual convention.

Saturday was an almost-perfect weather day in NJ, sunny, warm, with low humidity. The sun was perhaps a bit too warm, as I pulled my ’67 GT 1300 Junior out of its stall so that we could work on the Spider in the cool shade of the garage.

Enzo had the correct oil with him, 75W-90 GL-5 gear oil, so we decided to start with the gearbox. Jacking up the front of the car under the front spring perches, sturdy jack stands were placed under the jacking points just behind each front wheel. For some reason only known to Alfa engineers, the transmission case drain and fill plugs are on the same side as the exhaust (the driver’s side), so I found it easier to slide under the car from the passenger side and avoid contact with the still-hot exhaust pipes.

Enzo read the printout he had with him from his electronic service manual: “Remove the drain plug; allow the oil to drain out until you see just a drip. Reinstall the drain plug. Remove the fill plug, and add the appropriate oil until it reaches the top of the fill plug; reinstall the fill plug”. It sounded too easy.

On my ’67, I knew that the fill and/or drain plugs required Allen wrenches, as I had done this job on my own car a few years back. I also knew that I had a rather good assortment of metric Allen sockets. I grabbed my drain bucket and positioned it under the tranny. At this point, I related a lesson I had learned a long time ago, and possibly had witnessed during my own repair travels.

While the instructions were clear enough, I said, they should not be taken so literally. What if the car owner removed the drain plug, drained all the oil, reinstalled it, and then found out that s/he could not remove the fill plug? ROOKIE MISTAKE!

An experienced mechanic would always remove the fill plug first, just to ensure that it could be unscrewed and reinstalled. Having done that, the repair person would have the assurance that fresh oil could be added after the old oil had been drained. So that is what we planned to do.

Peering at the side of the case, flashlight in hand, I saw that the drain (lower) plug required a regular socket, perhaps 19mm or 22mm. But the fill (upper plug) would need an Allen (hex) wrench. I asked Enzo to hand me an assortment of metric Allen sockets from my toolbox.

None of them fit. Most were too small; one was too large. (This too-large one was 14mm, and I’m certain that I purchased it specifically for my car.) So much for my presumption that my ’67 and his ’91 would use the same size tools. I slid out from under the car, and opened a drawer which consisted mainly of Allen keys, in both SAE and metric sizes. I grabbed a bunch, got back under the car, and tried them one by one. None fit. That’s it, I said. We are finished before we even begin.

With that, Enzo opened his car’s trunk and rummaged through the tool kit that came with the Alfa. He pulled out a hex wrench. “Try this one” he said. I did. It worked. Voila! His Craftsman 12mm Allen wrench he just happened to have with him was the “key”.

This wrench was about 5 inches long, and working on my back, I didn’t have a lot of leverage to crank counter-clockwise on this thing. “Get me a breaker bar” I shouted. “There are some black iron pipes in the same drawer as my hammers”. Enzo gave me a pipe about a foot long. STILL could not budge the upper plug. I’m not the strongest guy to have turned wrenches, which is why I keep an assortment of breaker bars on hand. But this fill plug was F.T.

Enzo said “I have an idea – you hold the wrench and the breaker bar, and I’m going to extend my foot under the car”. Before I could ask him exactly what he had in mind, Enzo pushed hard with his leg against the pipe, and we both heard that satisfying “crack” sound when something that’s uber-tight breaks free. We did it. With the upper plug out, the lower plug was quickly removed with a 22mm socket and ½” drive wrench, and the old, possibly original, gearbox oil was flowing out and into my catch can.

I had forgotten to mention to Enzo the need for fresh copper washers, but I just happened to have a few new ones on hand. I think that every drain plug on every ‘60s/’70s Alfa uses the same size copper washer! The magnetic drain plug had a bit of sludge on it, but it didn’t look like anything to worry about to me. I cleaned off the sludge, and gave the threads a quick gentle scrub with a brass brush.

The drain plug was reinstalled, and Enzo snaked a rubber hose from the engine compartment, down toward the transmission. I held the hose in place at the fill plug, while Enzo poured in about 2 quarts of the gear oil. Once it started flowing out of the top hole, indicating a full tranny, I reinstalled the fill plug. This transmission drain-and-fill, with the jacking, prying, and filling, took us over an hour and a half.

The rear axle, by comparison, was relatively easy. Besides, we were now experts. The jack stands were removed from the front. The floor jack was placed directly under the differential drain plug, and both sides of the car were lifted at the same time. With the jack stands in place at the rear, I noted that we needed the same two tools: a 12mm Allen for the upper fill plug, and a 22mm socket for the lower drain plug. We again needed Enzo’s muscular right leg (probably built up from years of playing soccer) to loosen both the fill plug AND the drain plug, but with that. the rear axle oil was flowing.

This magnetic drain plug had the same amount of sludge, and it too was cleaned and fitted with a fresh copper washer. With the drain plug back in, we were ready to add new gear oil.

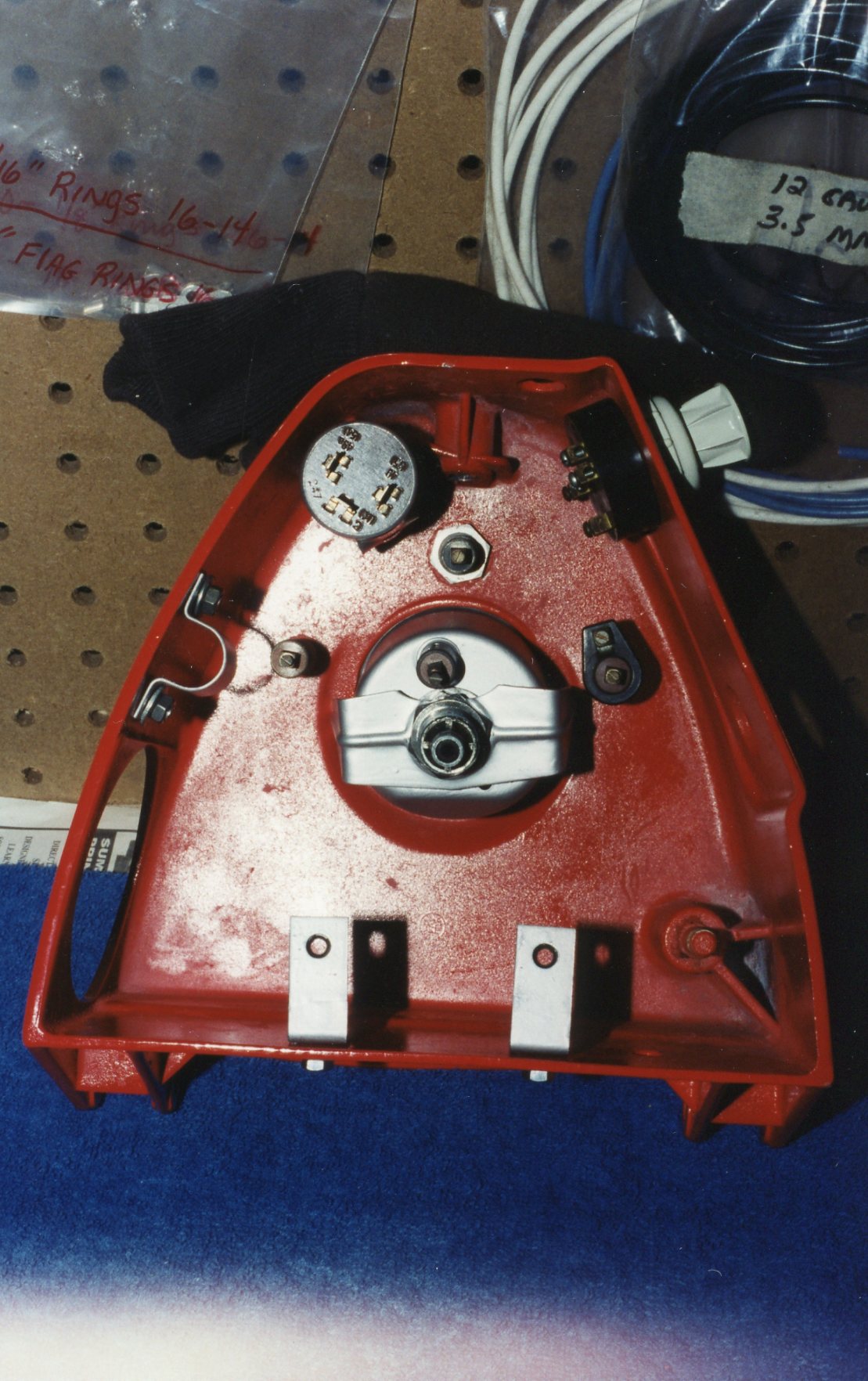

To route the fill hose, Enzo pulled the spare tire from its well, and unbolted a drain cap, which then provided excellent access to the fill hole. About 1.5 quarts of oil were added. We buttoned up, cleaned up, and started it up. A short test drive confirmed no untoward noises, and with that Enzo was safely on his way. Let’s hope there isn’t too much more to do between now and our mid-July departure for Pittsburgh.

SIDEBAR: THE ALLEN MANUFACTURING COMPANY

Most technicians are familiar with a tool that’s commonly called a “hex key” or “Allen key” or “Allen wrench”: it’s a six-sided hexagonal shape that’s inserted INTO a screw head or bolt head, as opposed to the more-common socket or wrench, also 6- (or 12-) sided that’s placed OVER the outside of a bolt head. The hex/Allen design offers the advantage of a smaller head that can fit in tighter places, and can even be designed to thread down and into a threaded hole or shaft.

“Hex” of course means “six”. But why is this tool also called an “Allen wrench/key”? You can thank Mr. William G. Allen, who, in 1909-1910, patented the design, and began manufacturing both the screws and the tools via the Allen Manufacturing Company of Hartford, CT.

My father worked around production machinery for much of his professional life, and set screws which required Allen wrenches were very common. My father’s extensive collection of Allen wrenches in both SAE and metric sizes are now in my possession, and even include some plastic carrying cases bearing the company’s name.

You can read more about Mr. Allen, his patent, and other related bits of information, in this Wikipedia entry on hex keys.

All photographs copyright © 2019 Richard A. Reina. Photos may not be copied or reproduced without express written permission.